The Common Good examine silicosis and speak with Respiratory Physician and Professor of Respiratory Medicine, Daniel Chambers and Research Fellow, Dr Simon Apte.

Walking to the top of the backyard never used to feel like this. You’re short of breath. There is also that cough that won’t go away. It reminds you of the times when you felt those sharp pains in your chest. All of this has been getting worse…

These are some of the symptoms of silicosis, an incurable and often fatal lung disease caused by exposure to silica dust. Many people may not even realise they have the disease because in the early stages, there may be no symptoms.

In Australia, silicosis has become an epidemic and has been described as the worst industrial health crisis since asbestosis. Typically, workers are exposed to silica dust while dry-cutting silica-enriched engineered stone, mostly used for kitchen bench tops and bathroom vanities.

Breathing in silica crystals causes scarring in the lungs making the delicate lung tissue stiffen. As a result, people have more trouble breathing because their lung capacity reduces.

Over time, the symptoms of the disease progressively worsen. According to Respiratory Physician and Professor of Respiratory Medicine, Dr Daniel Chambers, there are no existing treatments for silicosis. In the case of terminal silicosis: “The condition of patients’ lungs quickly deteriorates. In a few years, their only option is a double lung transplant,” he said.

Over time, the symptoms of the disease progressively worsen. According to Respiratory Physician and Professor of Respiratory Medicine, Dr Daniel Chambers, there are no existing treatments for silicosis. In the case of terminal silicosis: “The condition of patients’ lungs quickly deteriorates. In a few years, their only option is a double lung transplant,” he said.

However, 5 year survival after lung transplantation is only 70%, and 10 year survival 40%. With these kind of statistics, new preventative strategies and treatments for silicosis are desperately needed. That is why Professor Chambers and Dr Simon Apte are leading research into the disease through The Common Good, an initiative of The Prince Charles Hospital Foundation.

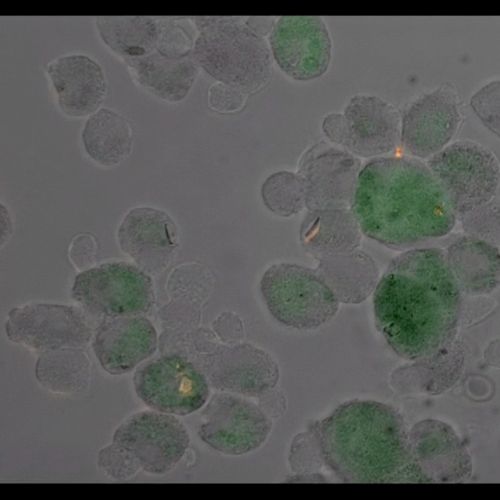

Dr Apte has already developed a world-first test to measure the amount of silica in a patient's lung. “This test could then be used to measure the success of a treatment called a Whole Lung Lavage. Using nanotechnology we can also fingerprint the silica crystals in the lung to see where they came from and why they are harmful,” says Professor Chambers.

“Whole lung lavage is performed under a general anaesthetic while the patient is kept alive on a ventilator. One of their lungs is washed out with 25 litres of salty water.

“Think of it like having a nail in your foot,” says Professor Chambers. “If you leave the nail in your foot and you just treat the symptoms of the problem, like the build up of scar tissue, then you’re never going to actually fix the problem.

“But the Whole Lung Lavage is like taking the nail completely out. We’re washing out the silica, and we’re washing out billions of damaged cells. The body will replace these cells with new, undamaged cells.”

Right now, this is the most promising treatment for silicosis. There are other potential drug treatments, but it would be incredibly expensive to put them all through clinical trials and discover the most effective. Instead, Professor Chambers and Dr Apte believe that an effective treatment is within their grasp. Even better, using cutting edge technologies they can study the extracted cells and crystals to design effective drug treatments for patients with residual lung scarring.

“Put it this way, if I was a disease like silicosis, I would be very afraid of the research we are doing here,” Professor Chambers said.

“We believe that we can solve this problem relatively quickly, if we get the research funds. There is genuine hope that this could be a transformational treatment.”

“And it’s not often that you hear researchers say that!” Dr Apte adds. “We’re normally very cautious about what can be realistically achieved. But we genuinely believe that we’re on the brink of something special here.”

To find out more about symptoms of silicosis and treatment or to donate to support this research, please visit thecommongood.org.au

Images from top: Silica crystals in lung cells (Credit: Dr Simon Apte), Professor Daniel Chambers, Dr Simon Apte